I recently spent several hours at the Yale Art Gallery for the Kirchner/Munch exhibit with friend and fellow teacher and writer, Saul Fussiner, who currently directs the writing program at the Educational Center for the Arts, where I have returned to teach. Saul knows of my love for expressionist art, and especially the paintings of Kirchner, and had been encouraging me to go all spring—and he finally called and offered to accompany me on the last day of the exhibit, and for that I thank him.

The Kirchner works consisted mostly of woodblocks and sketches lacking the characteristic bright and even garish colors of his paintings, which were all new to me and remarkable, but there were a few, stunning pieces featuring his unmistakable, “mis-coloration," stark, daring, angular lines.

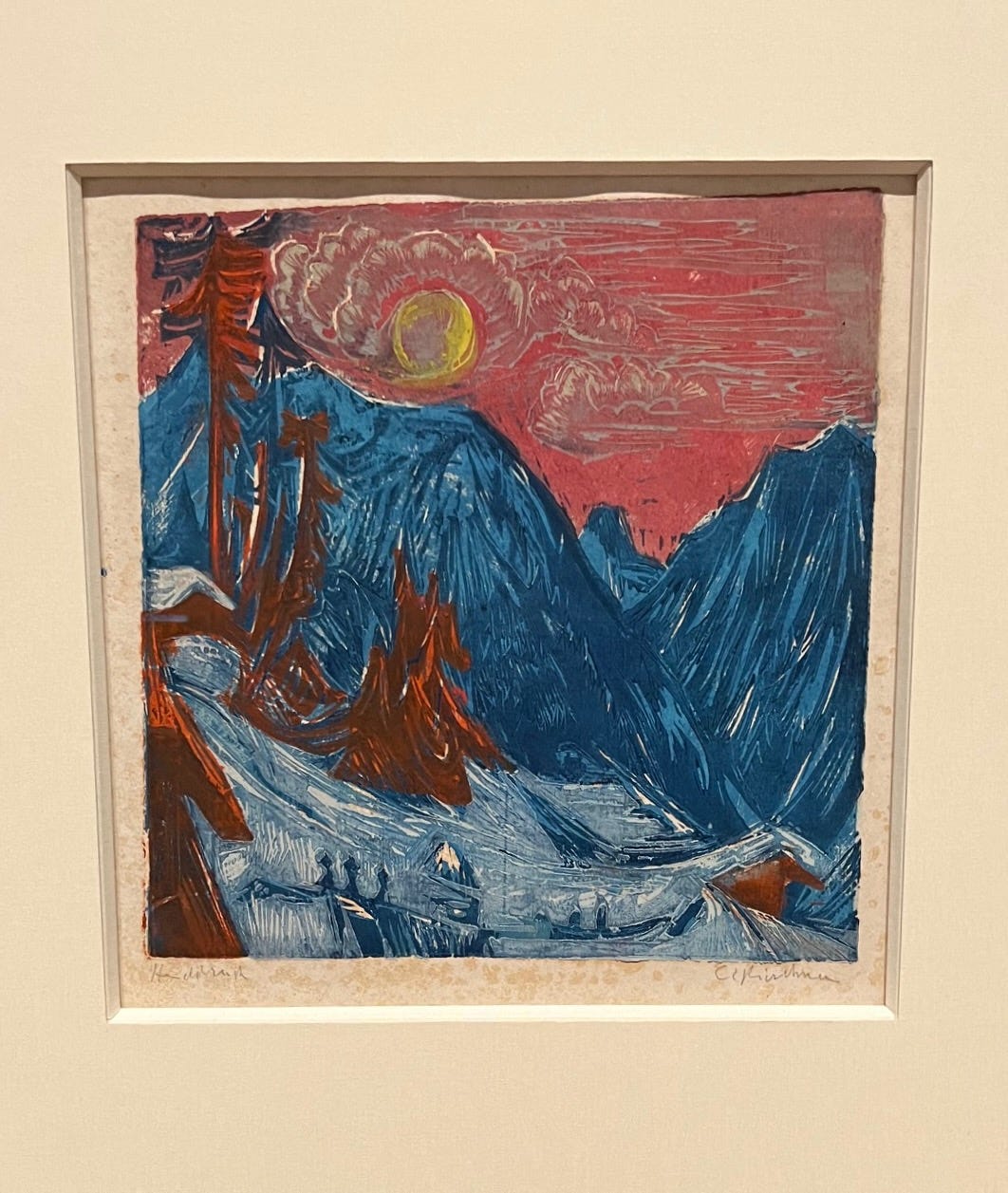

I was especially drawn to Moonlit Night, Winter. The woodblock is from the view of his mountain cabin, and the placard alongside the painting told me that he described the scene that inspired the work to a friend and sometime student as “simply, madly beautiful.” In the letter, he spoke of the “mountain all blue, the sky reddish violet with pink clouds, and the yellow crescent moon.”

I have always thought of expressionistic art as works where artists worry more about expressing emotion than about depicting the actual thing witnessed, and color with Kirchner seems especially “expressionistic,” but here, I was fascinated that Kirchner uses the colors he saw and described to his friend, that in some sense he had set out to “capture” the moment with paint and brush strokes. There are the blue mountains. There is the pink sky, the yellow moon.

I thought of the painting recently after making my first foray of the year into a small lake near my own cabin in my own Adirondack mountains. After a third of a mile canoe carry in, the lake appeared, blackish-blue through the deep greens of the pines, and in the midday light, the quiet of the pine-needle-carpeted trail, the surrounding hills blueish-green, the sky a resplendent blue, it was “simply, madly beautiful.”

I wondered, as I often do, what it would take to “express” the emotional experience of coming down the trail, my canoe balanced on one shoulder, my fishing rod and paddle clanging against the gunwales, my pace quickening as I finally reached the shore, lowered my boat in, set my gear into place, jointed my fly rod and paddle, stepped into the cold, tannin-brown water and lowered myself down into that familiar seat, then set off into the wind and near-white-capping waves of an early July day.

A photograph will rarely do. A simple recounting of events in language will rarely do. In any given moment, we are all of us immersed in something so rich, so mysterious, so “madly beautiful,” that the depiction of that moment will never be fully expressible through some other medium—words, paint, photography, film….

What seeing these works, and especially that one, small woodcut, caused me to consider was how artists must do something new, something that is itself an utterly, “madly beautiful” and immersive experience in order to bring viewers, readers, audiences to some facsimile of the power and emotional charge of the actual, remembered/experienced moment.

Kirchner takes those “blue mountains” and emphasizes the blue above all else, all formal, “representational” depiction of those mountains forgotten. His pink clouds and yellow moon and reddish sky become jarring explosions of those colors, lines, shapes etched from the heart of the emotional experience, so that the painting itself reaches out and touches us in something that approximates the way that moonset at dawn reached out and touched him. In a strict sense, he is being “representational,” even though the painting itself “looks” like nothing you’ve ever seen before in the lived world.

But when you really look, when you notice—and for me, the lone occupant of my small lake save for the occasional loon, the screech of a hawk, the vocalizations of a shore-bound but unseen raven, and the wash of light green and sparse, dying pines in the stretch of swampland that runs right to the base of the near hills, the bright gray of the boulder-strewn shoreline, the heart-shaped leaves of the water-plants that clog the lake’s outflow (I need to learn their name)…—you realize that the enormity of experiencing the present moment in a place of extreme beauty, or perhaps in any place, at any given moment when you really pause and look, might only possibly be conveyed through some parallel means, through the creation of something with its own mad beauty.

If you’ve been enjoying my writing, please consider doing any/all of the following:

Help me grow my audience by Sharing this post or my main site with a few people you think might enjoy it as well.

Upgrade your subscription to paid. For only $.14/day, you can help me continue to devote the many hours I do each week to writing, editing and promoting this page.

JourneyCasts is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

You can also help a lot by making a one-time contribution at any time by “buying me a coffee” (or two). And certainly a good amount of real coffee has gone into the making of JourneyCasts.

As always, I encourage you to leave a comment.

Be sure to check out my podcast, “Hemingway, Word for Word.”

Glorious! I reckon you’ve come pretty darn close to re-presenting that moment for us. I’ve just finished reading The Song of the Earth by Jonathan Bate - have you read it? It’s literary criticism (so I’m sure you will have) and develops the argument that the world needs poets, or rather ecopoetics, to bring us as close as we can get to the divine mystical experience of life. It’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about recently and you’ve expressed it perfectly here.

Saul is a wonderful catalyst.