"We Live Inside a Dream"

(David Bowie as Phillip Jeffries, in Fire Walk With Me). A fond farewell to the ultimate maker of dreams, David Lynch.

My love for David Lynch spans back to graduate school, and then the years immediately after that, taking my first teaching job at the University of Maine in Presque Isle. Presque Isle, far, far—far—north of Boston (nearly 8 hours of driving in good weather), proved to be the perfect place to watch Lynch’s ground-breaking television series, Twin Peaks way back in 1990. Presque Isle was itself already a surreal place, where the northern lights came nearly every night all January and February, snow piled higher and temperatures dropped lower than we had ever thought possible…and then when it did finally warm in spring, biting insects appeared in apocalyptic swarms... It all felt a kind of eerie extension of the much-stranger-still world of Twin Peaks, Washington. Back in those days, the one television station in Presque Isle had special dispensation from the FCC to broadcast their selection of programming from any of the three major networks; not surprisingly, they chose not to include ABC’s eclectic, surreal, dark, disturbing…(there aren’t nearly enough adjectives to fully describe Lynch’s artistic vision) Twin Peaks.

My mom, living in the civilized world of upstate New York, would tape an episode for my new wife and me and drop it in the mail, and we’d wait, each week for that big, brown envelope to appear—eerily like the mysterious VHS that appears every day at a character’s door in Lynch’s Lost Highway, I realize now! We’d pop popcorn, gather in front of our old Sony tube television, push in the VHS and wait for that haunting music to emerge from the TV’s one crappy speaker.

Reflecting on that year now, it seems all the more “Lynchian” itself, a young professor and his wife renting what would one day become a garage for a large house, now a makeshift, cabin-like structure with only its one big, creaking wood stove for heat, with their two cats and one dog, he navigating for the first time the halls of academe, she working hard to find a way to apply her Biology degree—so getting in a van with other employees of the state potato seed development labs, driving farther still out in the wilderness to avoid any possible contamination, the local people talking in their far north Maine accents, the “yahs” from down east morphed into just a quick intake of air, so when you’re in conversation with someone, they regularly make that abrupt inhalation, an almost comedic gesture—a gesture Lynch would have loved, the normative moment suddenly become odd, off kilter, dreamlike.

And there also, in front of many storefronts, were electrical outlets, female ends of extension cords strung down along parking meters for you to plug in your car in winter—no, there were no EVs back then. This was for you to plug in the heater core that would keep your engine warm enough to start in the other-worldly cold. There people drove to restaurants on their “snow sleds” and left their snow suits on, just unzipping them and letting them dangle down as they shuffled across the floor. There we saw our first moose after letting our dog, Baxter, out one cold morning, and he dashed away after something, and I followed, seeing it then, massive, gangly, all legs and antlers and that impossibly large head, taller than a tall horse, loping away across the road and the potato fields, Baxter in chase for a bit before he finally heeded my call and returned home. Wonderful, strange, unfamiliar, eccentric, new… All the words that describe our time there also describe the world of David Lynch.

It’s no surprise that Lynch became such an important part of my life then, and he has remained so all these many years. While some friends, acquaintances and students look at me a little askance when I praise even his more outrageous creations, I can honestly say he is one of the artists I have admired most in my lifetime—inclusive of all the artists I’ve known, living and dead.

I wasn’t surprised at all recently when I happened upon an interview David Foster Wallace gave with Charlie Rose, and he spoke of the influence Lynch had on him as a writer. He told of how everything he was doing seemed invalid, as if he were trying to figure out what he was supposed to do as an artist, what others expected him to do, how to crack the code, until he saw Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and everything changed. Lynch showed him that an artist only has to be true to their own vision, their own dreams, and they are only beholden to staying true to those deep, inner chasms of self that find their way “out” through art.

In one of the many interviews Lynch gave, he spoke frequently of finding “ideas.” He likened the desire to find an “idea”—and by this I think he meant, something you needed to—could only—give voice to through art—as being like baiting the hook when fishing. Then, when you first get the idea, a bite, he said it was only a mere fragment of the entire “thing,” but you could now add that fragment to the hook and keep fishing. When Lynch spoke about making art, what he said was so simple and understated that it hardly seemed appropriate when you then witnessed the often gargantuan absurdity and pure, raw power of his work.

I think what my wife and I embraced so fully sitting back in our double bed watching agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) drive into the town of Twin Peaks, talking into his small tape recorder to his often-referenced but never-seen “Diane,” was just how new he always managed to make everything seem. The worlds Lynch created were never quite our own world, and yet they somehow helped us see all the quirks and weirdness (and beauty) in our surroundings more acutely, this all the more relevant to us given that our own surroundings, far from the “normalcy” of Amherst, Massachusetts, where we had been for my 4 years of graduate studies, now seemed in many ways equally weird, and perhaps more importantly, deeply new.

A scene from that first run of Twin Peaks stands out in my mind. David Lynch himself playing the role of agent Cooper’s boss, FBI director Gordon Cole is at the Double R Diner. Gordon is deaf and wears an odd contraption as a hearing aid device. When the young, beautiful waitress, Shelly (Mädchen Amick) starts talking to him, he removes one headphone, and says, “I can hear. I can hear you…It’s like a miracle!” his words for the first time in the series not shouted. When the nearby “log lady” (Catherine Coulson) (a woman who has psychic powers and is told “things” by the log she carries with her wherever she goes), says, “What’s wrong with miracles…this pie is a miracle,” he returns to shouting and clearly can’t hear her. Finally, Shelly, the beautiful waitress, restates back to him what the Log Lady has just said…. For all of Lynch’s focus on evil and darkness, on the nightmarish unknown desires and passions of the human heart, he was equally drawn to beauty, the miraculous, the magical, those small things like hearing an actual human voice landing directly in your ears, not coming through the cords of a machine. Lynch’s artistic voice feels like that to me, as if something more real and complete and untranslated through any other devices were landing upon me directly in a way I had forgotten.

You can find moments like this everywhere in Lynch, even in his deeply disturbing (and powerful) first major film, Eraserhead, where the main character is as moved by the beauty of his mysterious neighbor as Gordon is by Shelly’s beauty.

But what really provokes me is just how willing he always was to let his imagination take him anywhere it led, to pursue what he liked to call his “ideas” to their unique, strangely beautiful and provocative ends. I’m also moved by how he worked, especially as a filmmaker, to create a dynamic, expressive tone through the seamless blending of his starkly expressionistic, often surreal cinematography with the haunting uses of sound and music (thanks to long-time collaborators Alan Splet and Angelo Badalamenti) and the often illogical, nonsequitur-laden originality of his scripts.

It’s hard to explain beyond this what it is one loves about David Lynch, which has not stopped many a film critic from trying; and the Internet—Reddit especially—is filled to the brim with theories and postulations about nearly every image and gesture in Lynchland. Find HERE a particularly engaging interpretation of the infamous two and half minute single take of a man sweeping up peanut shells from a barroom floor at the end of the 7th episode of Twin Peaks, the Return.

While I agree that one can easily find metaphors and symbols aplenty in Lynch’s work, one is also, always, firmly aware that his works resist “interpretation”—and by this I mean translating the whole emotional experience of Lynchian expression into standard, logical arguments. The “sweeping scene” fits somehow with the entire emotional, tonal landscape Lynch has created in his truly astounding cinematic effort of the 18 “episodes” of Twin Peaks the Return he made in 2017-18, each “episode” very nearly feeling on par with a full feature film itself. For me, the scene doesn’t need to be “solved,” and I vividly remember the experience of watching it for the first time. In a scene where nearly nothing happens, the music and lighting and stillness of the camera as the man sweeps for some inexplicable reason extend far beyond mere interpretation of the peanuts as symbolic of all the ugly things we’d like to, but can never sweep away in this world. I was left in rapt attention, feeling, as I so often do when watching Lynch’s films, as if I were stuck in a dream that I had no control over, a dream that was moving right from the core of Lynch’s psyche into mine. I never feel as if I’m being asked to solve anything with Lynch—to shift over to trying to restate that onslaught of imagery and sound into something else, something other than what it is.

A still more inscrutable experience comes from watching any of the many minutes of Lynch’s Rabbits, which first appeared as a “serial sitcom” on his website, davidlynch.com, and was later included as a scene in his film Inland Empire. I could try to describe the scene, the provocative, unnerving hum of sound, three disturbing rabbit-like costumed? characters, one ironing in the background, a female, another two seated on the couch, a male and female, how the male stands and says, “I have a secret,” followed by an uncomfortably long pause, a building of the humming, eerie sounds, the seated rabbit turning toward him, looking up, and nonchalantly saying, “There have been no calls today,” the live audience erupting into raucous, typical sit-com-style canned laughter… But that does little justice to the experience of seeing it, so I’d encourage you to take a few minutes and watch some of it here—even just a few minutes to get a sense of it. I love showing it to creative writing students as a way to emphasize how the language of art should perhaps always avoid direct translation into logic and reason, that artistic expression is more about tone, about communicating in its own language, one we all somehow recognize and “understand” at a level well beyond normative language.

An often neglected aspect of Lynch’s vision was his fondness for absurdity that suddenly morphs into humor (and then into the sublime). All throughout his work, from the mechanical waving of the fireman and the odd, robotic robin in Blue Velvet to the concurrently disgusting and hilarious “dancing lady in the radiator” scene in Eraserhead, we find his dark sense of humor. In his (also indescribable) short he did for Netflix, and the last film project he left us, I believe, What Did Jack Do?, clearly we are being invited to laugh, even as just beneath that laughter is something else, something unnamed that somehow the experience of the film starts to name for us.

Take, for instance, the extremely weird and off-putting “special effect” of superimposing human lips on a small, capuchin monkey engaged in a nearly indecipherable dialogue (obviously in Lynch’s own, mannered voice), Lynch more obviously playing the detective interviewing the monkey about his possible role in the death of a man involved with his former lover, a chicken named Toototaban! For me, the film is a marvel of expressionistic, surreal art—even as we come to a spit-your-drink-out-hilarious “lost love” song sung by the monkey with that disturbing human mouth under a gauzy spotlight and scratchy film effects. Find a clip of that scene here, but do take 17 minutes of your time to watch the whole thing on Netflix at some point. You won’t regret it, if not just for the comedic impact.

Lynch did engage in the more “ordinary" on occasion, as in his breathtaking The Elephant Man, where only hints of his Eraserhead-like vision arise—like when the camera hauntingly descends into the eye hole of the Elephant Man’s mask early in the film. And in the The Straight Story, Lynch utterly abandons his own interior meanderings and artistic whimsy to tell the true, powerful story of a man who drove his riding lawnmower across Iowa and Wisconsin to visit his critically ill brother.

Still, I get it when, like just the other night a colleague told me how much he loved Blue Velvet, but that “he couldn’t get into Twin Peaks, the Return.” My wife couldn’t finish watching Eraserhead, or Twin Peaks, the Return (even though she was an avid fan of the first iteration of the latter); and once, the day after an evening viewing of Eraserhead for a Film Noir course I was teaching, I came into the classroom to find scrawled across the chalkboard, “ERASERHEAD IS SICK, TWISTED AND JUST WRONG!!” Try as I may to spark a conversation based on how the Nazis had referred to some of my favorite painters—German expressionists—as “degenerate,” I couldn’t dissuade some of them of their opinions, which is fine. Lynch is surely not for everyone, and I wholeheartedly accept anyone’s negative response to him, though for me, this is another reason why I like him so much. As an artist, he never worried about trying to please the masses (except, perhaps, when shooting Dune). Rather, he concerned himself with finding the purest way to manifest his emotional interiority through his art, that world of “ideas” constantly swirling around beneath what another friend (and Lynch fan) has called “the best hair in Hollywood.”

Lynch was famously known for being an oddball in his “ordinary” life, though one could hardly guess that underneath his quirky exterior (and all that hair) lay so much complexity and darkness. He spent years only eating his meals at a nearby Big Boy restaurant, where he jotted out ideas for films—a different scene on each napkin. When he had 70 napkins, he said he had the complete groundwork for a film. He went through phases of only wearing the exact same brand and style of shirt and pants every single day, and throughout most of his adult life he’d settle on one meal, and only eat that meal every day for months, even years at a time. He claimed that by having his normal life be utterly predictable and unchanging, this would help unleash his deeper, interior self in his art. He sculpted, painted, made music videos, and even helped many of us get through the pandemic with his daily YouTube weather report (find his last weather report HERE). The Internet is awash with interviews with and anecdotes about Lynch, and it would be worth your time to surf around a bit and see what you might find (as I have been doing all morning).

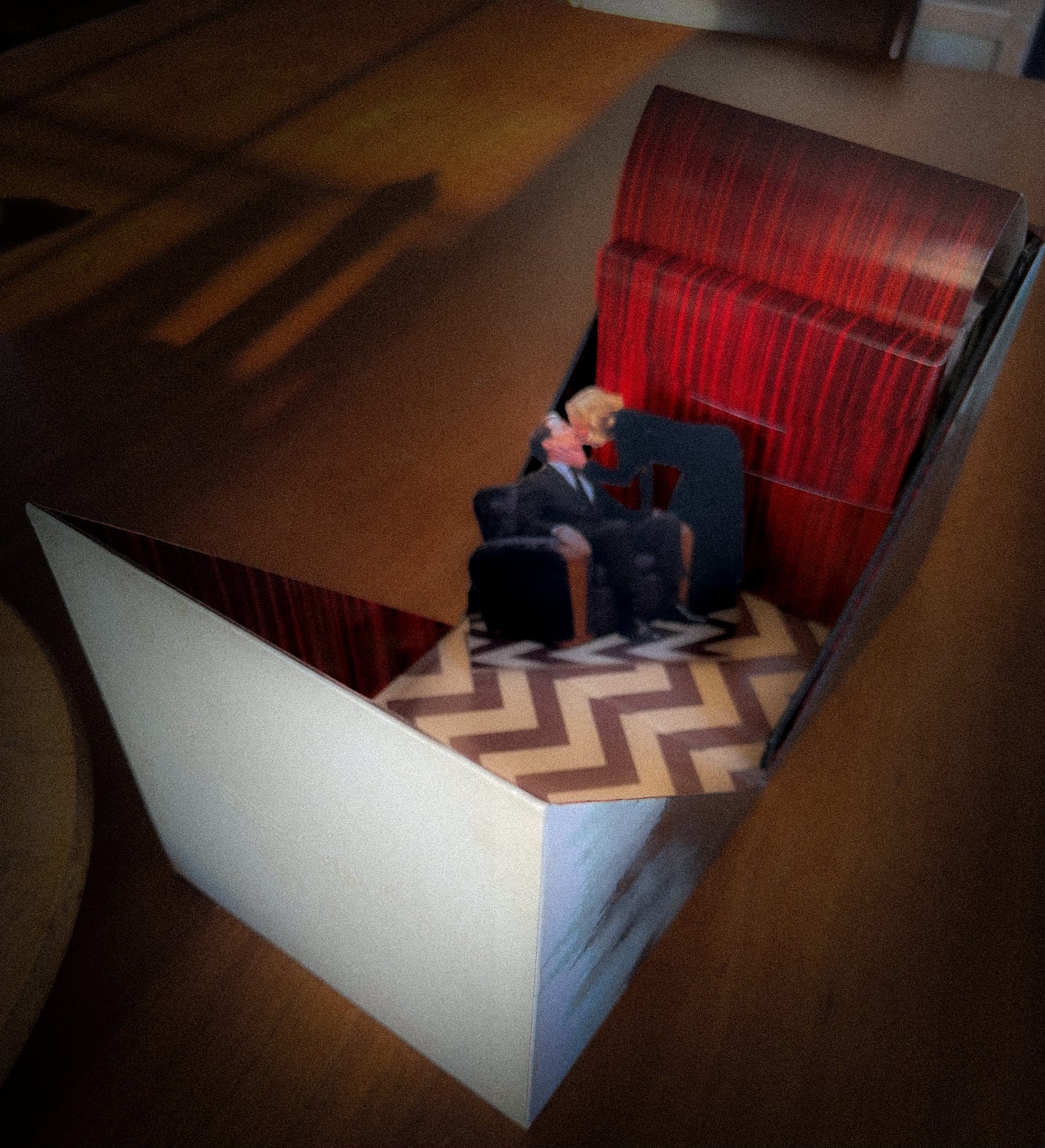

It was with great sadness that I heard of David Lynch’s passing yesterday in a text from a colleague as we sat in darkened arts hall listening to the young writers we teach practicing reading their poems and stories, essays, and screenplays for a public performance. It seemed a fitting place to receive the news, the dark curtains of the arts hall hanging still along the edges of the stage, the lectern and microphones standing alone in the center of the black stage floor, back lit by a blueish light coming through a translucent, backdrop curtain. I couldn’t help but think of Lynch’s own “red room,” from Twin Peaks, lined with its heavy, velvet curtains, that floor with its jagged black and white pattern, this perhaps most inexplicable of settings in Lynch’s inexplicable universe, where a dwarf makes odd gestures and does a twisting, strange walk-dance and speaks in a backwards, incomprehensible language, where Laura Palmer finally appears to Agent Cooper, leans over, whispers a secret in his ear, and gives him a tender kiss. I wondered if this was the place his consciousness fell away toward as the final curtain fell. Just as Laura says to him before the whisper we will never quite hear, “I am dead, yet I live,” Lynch will surely live on through the prodigious and astonishing work he left us even as he leaves us forever mystified and enthralled.

If you’ve been enjoying my writing, please consider doing any/all of the following:

Help me grow my audience by Sharing this post or my main site with a few people you think might enjoy it as well.

Upgrade your subscription to paid. For only $.14/day, you can help me continue to devote the many hours I do each week to writing, editing and promoting this page.

JourneyCasts is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

You can also help a lot by making a one-time contribution at any time by “buying me a coffee” (or two). And certainly a good amount of real coffee has gone into the making of JourneyCasts.

As always, I encourage you to leave a comment.

Be sure to check out my podcast, “Hemingway, Word for Word.”

What a great tribute to Lynch. I remember Twin Peaks from the ‘80s. How interesting that Lynch was such a creature of routine. Makes me feel justified in insisting that my own morning routines are necessary to elicit the creative ideas.